Projects

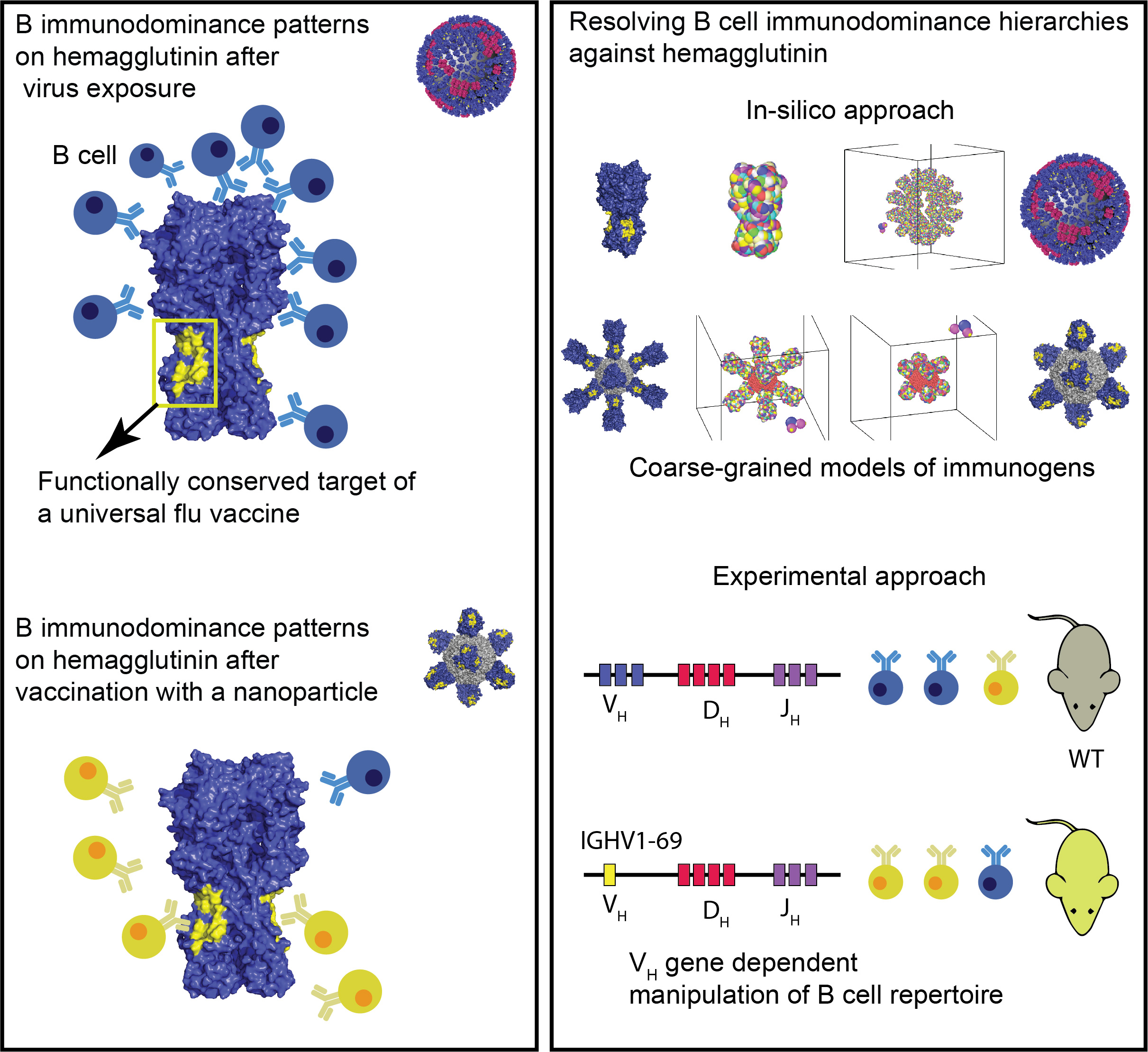

B cell Immunodominance and a universal influenza vaccine

The yearly vaccine against the influenza virus targets a protein on its surface called hemagglutinin (HA), which helps the virus to bind and enter the host cells. Following vaccination, the immune system generates antibodies that target HA and can neutralize the virus. Most antibodies target the head of the HA protein, which mutates rapidly and often escapes those antibodies. The stem of HA contains conserved residues that are the target of broadly neutralizing antibodies. Eliciting strong antibody responses against the conserved part on the stem would offer universal protection. However, those conserved residues are immunologically recessive and are usually not targeted by the antibodies. Using models of the antibody response against the virus, nanoparticles presenting HA, and experiments in mice we studied the conditions that would allow stem-specific broadly neutralizing antibodies.

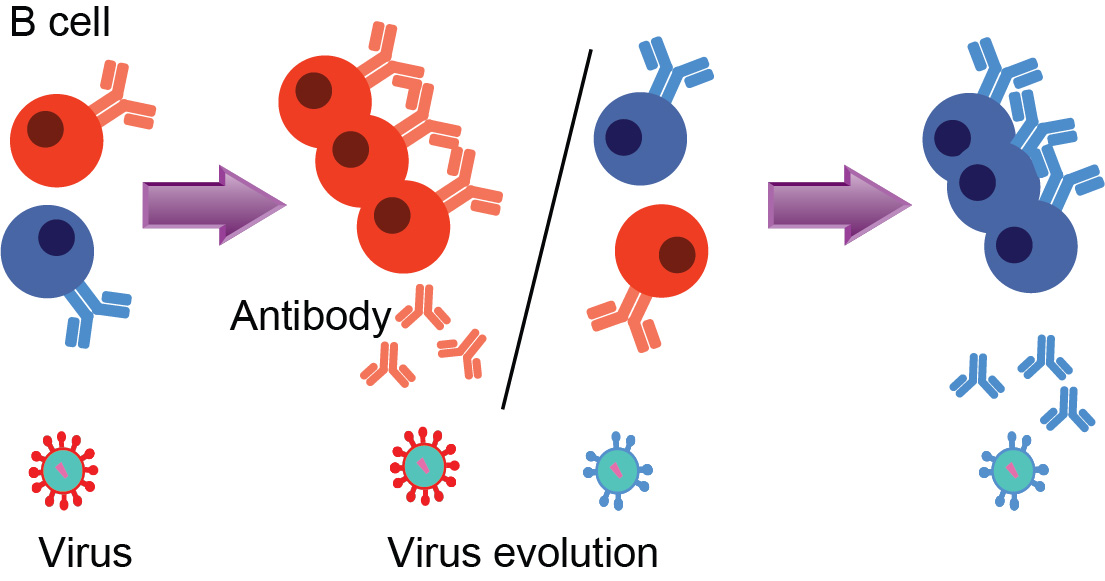

Affinity maturation drives evolutionary constraints on virus spike density

The spikes on virus surfaces bind receptors on host cells to propagate infection. High spike densities (SDs) can promote infection, but spikes are also targets of antibody-mediated immune responses. Thus, diverse evolutionary pressures can influence virus SDs. HIV’s SD is about two orders of magnitude lower than that of other viruses, a surprising feature of unknown origin.

In a recent paper, we try to explain this riddle. By modeling antibody evolution through affinity maturation, we find that an intermediate SD maximizes the affinity of generated antibodies. We argue that this leads most viruses to evolve high SDs. T helper cells, which are depleted during early HIV infection, play a key role in antibody evolution. We find that T helper cell depletion results in high affinity antibodies when SD is high, but not if SD is low. This special feature of HIV infection may have led to the evolution of a low SD to avoid potent immune responses early in infection.

You can find the affinity maturation code for simulation relevant for this paper here:

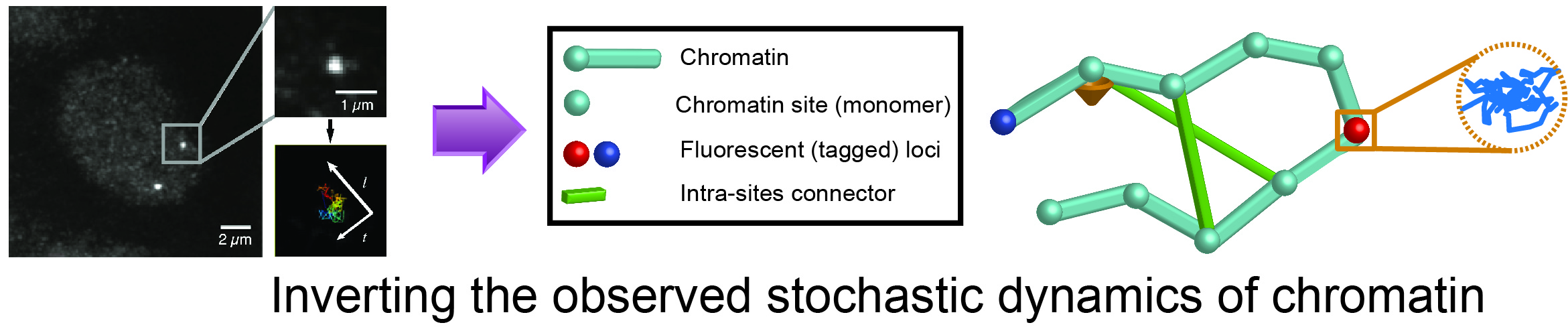

Modeling chromatin dynamics

The chromatin molecule resides in the nucleus of eukaryotes organisms. The principles governing its organization and dynamics are still largely unknown. Chromatin dynamics control the encounter rate between chromatin loci, which is consequential in many biological processes such as DNA repair, differentiation, and transcription.

Chromatin motion can be observed by fluorescently tagging sites and following them with high-speed microscopy to produce high-resolution trajectories. To decipher the principles governing the motion of chromatin, we developed methods combining polymer models and statistical inference to analyze these trajectories. We have shown, that following a double-stranded DNA breaks, chromatin structure and dynamics are modified to facilitate the repair of those breaks. We find that in general, the motion of chromatin is due to an ensemble of interactions of the molecule with its surroundings. Those interactions are being modified around the break during the repair process. As a result, chromatin opens locally to accelerates its motion and allow it to initiate repair via homologous recombination.

Cell Reports and Nature Structural and Molecular Biology

In those papers we describe a statistical method to estimate four parameters characterizing chromatin dynamics from Single Particle Trajectories (SPTs). We provide here our Matlab code to study the time-lapse imaging of single loci by fluorescence microscopy. The code can be applied to any trajectories of tagged DNA loci. The code allows extracting four biophysical parameters from the movement. The method can be used to study the changes following DNA damages or breaks and can be applied to single locus trajectories in any species.

A talk I gave about this work at the Isaac Newton Institute in Cambridge in June 2016

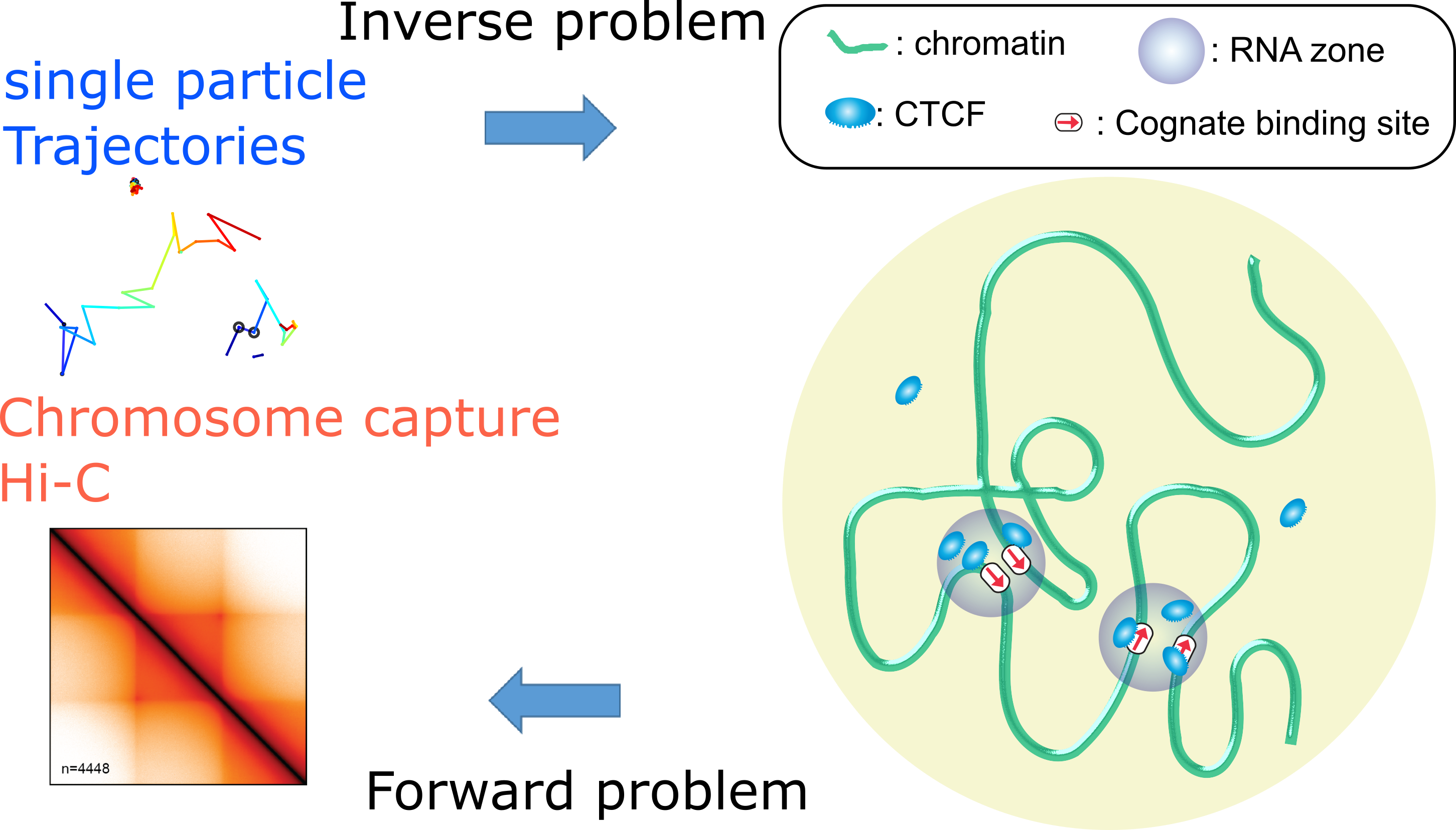

Modeling protein dynamics and its link to chromatin organization

The organization of the genome is governed by nuclear DNA-binding proteins such as CTCF and cohesin that mediate chromatin looping. Using single-particle tracking of CTCF in live cells and in collaboration with molecular biologists, we discovered that it exhibits highly unusual motion in the nuclear space. Modeling the interaction of CTCF with chromosomes, and analyzing its motion, we could infer the properties of the underline chromatin-bound structures with which CTCF interacts.

Our analysis of CTCF mobility revealed a new type of zones composed of RNA that modify the motion CTCF and are important to maintaining genome organization via chromatin looping. Importantly, those RNA zones decrease the time it takes for a protein to find its target (cognate binding site). Trapping of CTCF in zones increases the efficiency of chromatin loop formation. The interaction of other proteins with such RNA zones could be an effective way to control and regulate the local concentration of proteins in the nucleus around specific sites.

CTCF dynamics and search behavior

A population dynamics model for clonal diversity in a germinal center

Germinal centers (GCs) are micro-domains where B cells mature to develop high affinity antibodies. The GC is seeded by multiple (~50-200) initial B cell clones. Each clone has a unique sequence of the gene coding for the B cell receptor (BCR). This receptor later becomes the antibody in mature B cells capable of binding and neutralizing an antigen. During the germinal center reaction, B cell clones proliferate and create diverse lineages, where the descendent self-induce somatic hyper-mutations. Inside a GC, B cells compete for antigen and T cell help, and the successful ones continue to evolve and become memory and plasma B cells. We studied the competition between B cell clone using a simple population dynamics model of birth/death and mutation. We find that, like all evolutionary processes, diversity loss is inherently stochastic. We study two selection mechanisms, birth-limited, and death limited selection. While death limited selection maintains diversity and allows for slow clonal homogenization as affinity increases, birth limited selection results in a rapid takeover of successful clones.

Encounter events inside the nucleus

The DNA is subject to Brownian motion resulting from the interactions with the surrounding water molecules and is constantly moving inside a confined domain, which is determined by the cell or nucleus membrane. In recent years it has been understood that its dynamics and organization have significant consequences on the cellular functions. For example, the encounter between chromosome sites is directly involved in many biological processes, such as gene regulation and DNA repair. One important characteristic of these encounter events is their frequency. Since the interacting sites have to come nearby for the chemical interaction to occur and because the encounter is largely diffusion-limited, these events are inherently rare. The exact implications of these encounter events are still mostly unknown, but over the last decade microscopy methods and chromosome capture techniques have been developed for their study.

I have used simple models to study the encounter between chromatin sites in different scenarios. We first addressed the question of the encounter between two monomers part of the long chain in bulk (DNA looping). We have found for the first time, a complete mathematical formula describing the dependency of the mean encounter time, on the length of the polymer chain and the capture radius, which is the distance at which the sites meet. In a second work, we have looked at the way these rates change when the polymer chain is confined in a close domain representing the nucleus, or a chromosome domain. We found an analytical formula describing the dependency of this rate on the size of the domain. Interestingly, we find that encounter and looping can be very effectively regulated by controlling the domain size.

Analysis of the mean first looping time of a rod-polymer

Computation of the Mean First-Encounter Time Between the Ends of a Polymer Chain